"Doing the Impossible": A COVID-19 Vaccine Retrospective

by Rohan Shah

Rohan Shah

Princeton ‘20

"The Last Days of Rome." My friends and I spent our last nights on campus at our eating club, Cap & Gown, at Princeton University in New Jersey.

An Unknown Fate

When the coronavirus hit the United States, I was amid the delirium of my senior year at Princeton University. Just around the corner awaited the end of classes, the submission of my senior thesis, graduation exercises, and the nostalgic celebration of a very important four years.

The night President Eisgruber told us we would be having an “extended spring break” due to COVID-19, I was thumbing through restaurants in the late hours of the night in my dorm room to reserve a graduation dinner in June. When the email flashed onto my screen, I sat back in disbelief. I was aware of the coronavirus having kept up with the science and the spread. Jokingly, I had sent “Corona” beer-themed memes and other banter to friends. Some kernel of my mind, however, understood the severity of the pathogen and I was quick to portend that this situation would morph into something far worse than we could have imagined. While coronavirus might have been the buzzword on my tongue in those early weeks of March, the contagion felt light years away from my existence.

A day before that email, Harvard and M.I.T had told their students to essentially run far, far away from campus in what, at the time, seemed like unabashed hysteria. But as I stared blankly at that email and the press release on the University homepage, I was still stunned that we in Princeton, New Jersey, had met the same fate. It was hard to believe that the virus I had just learned about in Professor Ploss’ Molecular Immunology course was about to throw a wrench in the closing innings of my undergraduate experience.

Before I knew it, tears streamed down my face as I said final farewells to classmates, professors, and to the campus that I loved more than anything. The grief of having this experience pulled stirred deep in my gut and the anger at a microscopic, unobservable particle ruining what were supposed to be some of the best times of college was hot on my breath. Back at home in my childhood bedroom, the “teenage angst” poured out, leaving me restless and resentful. While many of you readers might know someone who had a similar go at it, only the Class of 2020 will truly know and internalize this lived experience.

Even so, it felt wrong to fixate on the impact coronavirus had on my life, while in early April it was stealing four hundred souls every day in my home state of New Jersey. Seeing bodies being wheeled out of nursing homes into refrigerated trailers, physicians collapse of exhaustion, and Governor Murphy cry on the nightly news was dreadful, frenetic, and bone-chilling.

Like with many other things in my life, I found not only solace but also power in understanding. Armed with my molecular biology education and experience in drug development, I found myself spending many of those lonely nights down the endless wormhole of coronavirus information, scanning Nature Medicine, Science, and Biorxiv to understand the genetics, the virology, the epidemiology, the physiological consequences, and much more about SARS-CoV-2. Nights of religious reading and scientific analysis soon translated into educating my parents and peers on what was true, false, and unknown about the contagion. By virtue of web conferencing, I even had the ability to launch into scientific discussions with experts around the world. Although people far more educated than I were dissecting and solving the problem, in those months of anxiety, knowledge felt like power over my life.

The Empire Strikes Back

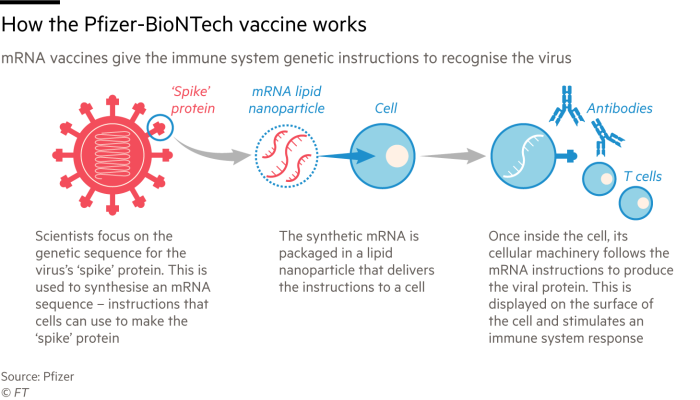

Hydroxychloroquine, dexamethasone, and even injecting bleach, believe it or not, were far cries from the panacea we so desperately hoped would end the crisis. Remdesivir showed promise, but as astutely captured by Professor Ploss, it was like “jamming a key into a lock but being unable to turn the key” in terms of inhibiting the viral protein that enabled infectivity. As the public health landscape deteriorated, it became evident to Dr. Anthony Fauci and others in charge that universal immunization would be the only light at the end of the coronavirus tunnel. Messenger ribonucleic acid, better known as mRNA, was thus thrust into the spotlight as an innovation that could deliver a safe and efficacious vaccine.

A BioNTech scientist tests BNT162b2 in preclinical experiments in Mainz, Germany.

Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech emerged as the frontrunners. Using the publicly available genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 as a blueprint, both efforts converted this string of adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine into a prospective vaccine in which mRNA molecules encoding for the viral spike protein were encapsulated in a lipid particle. When dosed into a human, the vaccines would elicit an adaptive immune response that would guard against a future SARS-CoV-2 infection. Importantly, these vaccine candidates only encode for instructions for the spike protein—not for the full viral genome, like other conventional vaccine approaches. Before you ask, no there’s no risk of being mutagenized, having the particle integrate into your genome, turning into Frankenstein, and, most importantly, there’s unequivocally no way of contracting the virus from the vaccine.

Moderna did this in about sixty days.

Think about that for a second. Vaccine design and optimization—a process that usually requires upwards of half a decade—happened in less than a season. Compare that timeline to Dengvaxia, a vaccine for the dengue virus, which earned regulatory approval in May 2019 after ten years of discovery and development. As noted in a recent New York Times cover article, the mRNA technology proved to be incredibly versatile, agile, and scalable. The dueling efforts sped forward from “bench to bedside” at the speed of light, even as the weight of the world descended on their shoulders.

To the dismay of the unaware and uninformed, however, creation of a vaccine candidate did not constitute immediate distribution and immunization. Instead, the long slog of clinical trials laid ahead, where the companies would have to prove in humans that the vaccines were both safe and efficacious to receive approval from global regulators. What did that mean?

Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech went on to structure event-driven clinical trials where half the participants would receive the vaccine and half would receive a placebo. Contrary to some fraudulent reporting, participants would not be “challenged” to the virus, intentionally inoculated with it, and instead would lead normal lives. As a result, the trial hinged on the vaccine cohort showing superiority to the placebo cohort by having fewer “events”—COVID-19 infections. Given the seeming randomness of COVID-19 infection, the trials had to enroll thousands of participants, with Pfizer/BioNTech ultimately clocking in at 43,186 and Moderna at 30,000. At prespecified event numbers, the companies could cut the data and see if the statistical significance of the vaccine arm over the placebo arm was indeed achieved. In collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Operation Warp Speed, the efforts mobilized to enroll willing volunteers in geographies most affected by the virus to more effectively prove the benefit of the vaccine.

The Trial of the Century

Around the end of August, Nature Medicine, an esteemed scientific journal, published the Phase I data of roughly thirty patients for each trial. Strikingly, both vaccines stimulated a high titer of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and had no severe safety signals. Reviewing these data, I leapt at the chance to participate in the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, which was about to launch an ambitious Phase III clinical trial and begin enrollment imminently. Through August and September, I called the Pfizer clinical trial hotline almost daily, feverishly asking about updates: When would enrollment open? What was the closest trial site to me? What was the trial design?

After weeks of persistence, a trial coordinator from Mt. Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, New York, called me and started to pre-screen me for enrollment.

“At this stage of the trial, we’re only enrolling certain populations. Are you elderly, immuno-compromised, HIV+, Hepatitis A, B, C+, or a person of color?” she spouted off on the call.

Being of South Asian descent, I leapt at the “person of color” denomination. I am convinced that my enrollment was contingent on this. In that moment, I felt hopeful and optimistic that I would be part of this incredible effort. But I needed to do my homework.

With the Informed Consent Form (ICF) in hand, I analyzed every sentence and pored over the referenced primary literature. Importantly, I then triaged opinions from my very own “expert network” by sending the form to the Chief Medical Officer, Chief Development Officer, and Executive Director of Biologics at my company, Loxo Oncology at Lilly, capturing nuances on the disease biology, the vaccine candidate itself, clinical development, and risk factors. Over more than a few video calls, I discussed and debated the merits of the vaccine, the potential side effects and liabilities, the trial design, and if this made sense for me.

Posing for the photo after my first dose at Mt. Sinai.

No one tells you what to do in these situations. You must make a judgement call in the end. Clinical trials are high stakes, as I knew all too well through my job. But in those moments of vacillation, I thought about a quote from Benjamin Franklin by way of the movie National Treasure: “those who have the ability have the responsibility.” I, a healthy, minority twenty-two-year-old with a deep understanding of this virus and vaccine, should step up. If not me, then who?

With that adage percolating in my mind, I sent an email confirming my desire to enroll. The next day, the coordinator said I was eligible but would only be able to enroll if I came up the very next day—a Wednesday, during the work week.

“Yes, of course, where do you need me to be and at what time? I’m there,” I said verbatim on the call, giddy with excitement as I cleared my calendar. I woke up early the next day, once again reviewed my notes and questions, and even dressed up for the visit. Although it was clear from the look in my parents’ eyes that they were hesitant about my decision, we did a prayer together as a family and I was on my way to Mt. Sinai. It felt like I was going to be a small part of something big, something that would stand the test of time, something that would change the world.

During that first visit to Mt. Sinai in late September, I found myself fidgeting in the waiting room of the “Experimental Therapeutics and Trials” unit alongside several other participants. We traded introductions, compared opinions, and tried to suss out insider information from those who were farther along in the process. Questions like “What dose are you on?,” “Do you think you’re in the vaccine or placebo cohort?”, “Is it painful?”, “Did you feel anything?” lit up our conversations. Believe or not, the excitement in the room was palpable.

When I was called back into the examination room, the attending physician came to explain to me the Informed Consent Form. By chance, that physician happened to be Dr. Judith Aberg—a renowned infectious diseases expert who was on the national steering committee for the vaccine. Like many others leading the charge, Dr. Aberg pivoted her expertise and efforts in HIV to address the coronavirus pandemic. As I peppered her with questions, Dr. Aberg started to explain all the intricacies and nuances of the contagion and the vaccine. When I pressed her about the approval timeline for the vaccine, she said something I won’t forget:

“Tony and I are trying to get this in front of the FDA as soon as possible,” she said.

“Who’s Tony?” I responded.

“Tony Fauci? You’ve probably seen him on TV,” she said without hesitation.

I couldn’t believe it. In that moment, I realized that Dr. Aberg was one of a handful of people worldwide who understood the COVID-19 pandemic writ large.

Once I signed the form, it was time for the actual “jab in the arm”. The nurses first captured my measurements, collected several vials of blood, and nasal-swabbed me while the pharmacists downstairs prepared the vaccine. Because the vaccine is stored at -80°C, the thawing and preparation process took nearly an hour. Moreover, all identifiers on the dose had to be removed to comply with the double-blinded design of the trial. Neither the participants nor the attending physician could know. Only the study nurse would know what I received, just in case I had an immediate adverse reaction. At last, the nurse flicked the needle, rolled up my sleeve, and intramuscularly injected BNT162b2—the vaccine candidate.

Right after the vaccination, I was placed in a waiting room where the nurse would monitor me for an hour. During that time, she oriented me to my “study packet,” which contained a thermometer to use in the event I felt ill, a self-nasal-swab kit to send Pfizer if I suspected infection, and instructions for onboarding TrialMax, a phone app that would survey me every week for symptoms.

I was told that if I had received the actual vaccine I would “feel something,” such as a low-grade fever, chills, aches, and pains. Within a day, I did feel a minor headache and aches but nothing nearly as severe as was described. An aspirin dissipated the pain. Perhaps the all too familiar “placebo effect” had me believing—no, hoping—that I had been immunized.

To Mount Sinai Hospital and Back Again

Enrollment into NCT04368728—the Pfizer/BioNTech Phase III clinical trial—meant far more than just that one visit. According to the study design, the trial would continue for two years and only halted if the agent demonstrated convincing safety and efficacy. Through both the TrialMax app and periodic visits, I would be in frequent communication with the trial coordinators and under close surveillance. While this might seem taxing, there are advantages.

Dr. Judith Aberg, Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases for Mt. Sinai, in her office in Manhattan, New York.

The most significant upside is early access to the vaccine. If the FDA greenlights the vaccine in a few weeks, Pfizer/BioNTech will “unblind” the study and tell participants whether they were in the vaccine or placebo arm of the study. If you got the vaccine, great! If not, it is almost guaranteed that trial participants who were on placebo will be “crossed over” or switched onto the real vaccine under the orifice of a new clinical trial. In that way, Pfizer/BioNTech can continue to study the safety, durability, and efficacy of the vaccine in a population of people already in their registry, providing long-term data that will go miles to give the public peace of mind. Although this was never a guarantee in the study protocol, Dr. Aberg and others made it clear to me that this historical precedent would probably be applied here to comply with patient ethical guidelines. As a reward for taking what many would deem a “big risk” on an unproven vaccine in the middle of a global pandemic, I will reap a priority voucher to get the real thing—probably six months before the rest of my age group.

The next upside is information. Now, Dr. Aberg and her colleagues cannot divulge “material non-public information”—information not available to the general public per Securities Exchange and Commission rules—but she and her team can give participants like me a better understanding of the information in the public domain. During visits and over email, the study team at Mt. Sinai has helped me better understand the design of the trial, the actual biology of the virus and the vaccine, the regulatory interactions, and the distribution, among other topics. In a world subsumed by the endless vortex of COVID-19 (mis)information, I feel privileged to have world experts just an email away.

The last perk is compensation. As part of the trial, I stand to make a nice $1,500 overall. I joked, however, that I would pay Pfizer/BioNTech to be in the trial. Just being part of this effort is priceless to me.

I would be remiss if not to express my gratitude to Dr. Aberg and her team in the Experimental Therapeutics and Trials Unit at Mt. Sinai. Even amid a global pandemic, and with the herculean task of running a COVID-19 clinical trial, the study team has been nothing but patient, informed, and kindhearted toward me. I very much look forward to continuing participation in this clinical trial, or an amended version, for years to come. Like the frontline healthcare workers, I believe the individuals running these trials deserve our highest praise: they are the ones who saved the world.

Reflections

My main motivation for writing this article stems from the many messages and calls I have received since Pfizer/BioNTech released their data. Some are hungry to understand more about the vaccine candidates and their associated clinical trials. Others, like my sister, are frontline workers who are anxious to be first in line for the vaccine. Although I am far from expert on this topic, for many, I might be the only person they know participating in one of these trials and who is so intimately familiar with the contagion. If I can be helpful, I will. Ahead are some of my reflections.

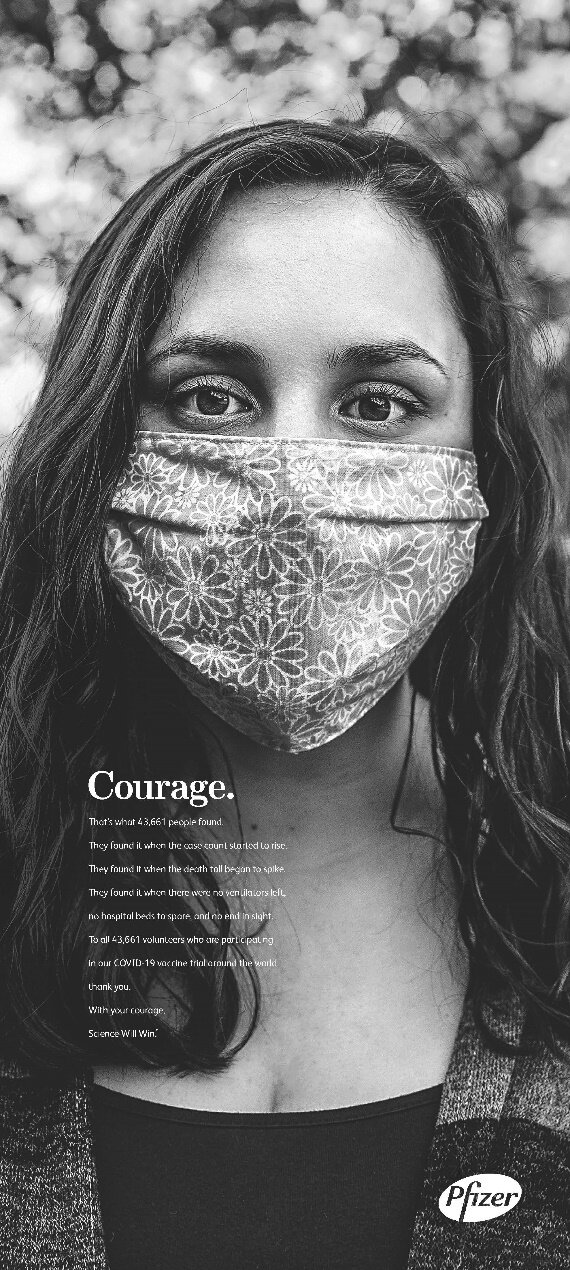

Pfizer's full page "Thank You" to trial participants in major news publications.

As we near a regulatory decision for both vaccines, I think it is important to underscore the gravity of what was accomplished here. To paraphrase a popular metaphor: what both companies did is like having never played baseball before, stepping up to the plate, and hitting a home run on the first pitch. Producing a vaccine with 95% efficacy—on par with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine which has been in clinical use for half a century—is a glorious accomplishment and beyond our wildest expectations. Though overshadowed—and perhaps rightly so—by the most consequential presidential election of our lifetime, the discovery and development of a coronavirus vaccine might just be the most important medical accomplishment of the twenty-first century.

Now, efficacy is not effectiveness. Best captured by Carl Zimmer of the New York Times, “from the headlines, you might well assume that these vaccines will protect 95 out of 100 people who get them,” but that is, in fact, a straw man fallacy. Whereas efficacy is the measurement made during a clinical trial, effectiveness gauges how well the vaccine works out in the real world. Though these barometers could match one another, it is more probable that the effectiveness will deteriorate as the vaccine is rolled out to millions. Reasons for this might include that the clinical trial did not mirror the diversity of the populace or that people with preexisting conditions may dampen the vaccine’s intended effect. Even if these vaccines end up being short of perfect, “keep the faith” and take what you can get. The alterative scenario is far worse…

Unfortunately, this scientific triumph has been politicized to no end. While I will not descend into that debate, I implore you to consider the paradigm and the facts. President Trump or President-elect Biden are not the final arbiters on this vaccine. Their words are neither golden nor paramount. The FDA, an independent regulatory agency with some of the most intelligent and integrous civil servants, will provide the ultimate approval based on data. As I spotlighted earlier, the data will have to convincingly support both safety and efficacy. Even then, the label “approved” will be an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), which says that the agent “may be effective,” but not that it “is effective”—a very important distinction.

While the public harbors intense distrust of the biopharmaceutical industry, the leaders steering the ship, such as Albert Bourla and Stephane Bancel, the Chief Executive Officers of Pfizer and Moderna, respectively, command organizations full of integrity, corporate social responsibility, and, most importantly, with an ingrained commitment to improve the lives of people. As someone who has just started a career in this field, I think I can tell you that most people in the biopharmaceutical industry are motivated by the chance to help patients. We should instead applaud the valiant efforts by Pfizer, Moderna, and many other companies who invested mind-boggling amounts of time and resources “at risk,” without the promise of success, to conquer a disease that was not at all their responsibility. That’s called answering the call of duty.

Even if you believe perverse financial incentives are accelerating the development of this vaccine, neither company stands to benefit from an ineffective agent in the long run. Such a result could ruin their businesses and jeopardize what little public trust remains. Given the magnitude of the public health crisis, the government, importantly, will be the “middleman,” purchasing vaccines at cost from Pfizer and Moderna. Through a mechanism like the CARES Act, which has made COVID-19 testing largely free, the government will likely cover any “out-of-pocket” cost to Americans—insured or uninsured.

With that in mind, consider yourself fortunate to live in a nation where the government has impelled the innovative private sector to harness new technologies for vaccine development, has subsidized arduous research and development, and will now ensure access to a vaccine. Only in the United States of America is this possible. Others around the world are far less fortunate and will either see their societies cower to the pathogen or gain herd immunity.

Stephane Bancel, Chief Executive Officer of Moderna, in his office in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The vaccine is not only the light at the end of the tunnel, but also the only way out. If, like me, you thirst to attend a concert, watch a football game, see your friends and family mask-less, or even graduate in person, all of us being vaccinated is the only thing that will save us. Akin to my enrollment in the trial, no one will tell you what to do. You must decide. But, please, make that decision on your own terms.

Upon seeing the Pfizer/BioNTech data cross the headlines a few weeks ago, a friend said to me that “science is cool again.” Let me be clear: science was never not cool. Through science, we, humankind, hold the power to understand and alter our existence. BNT162b2 and MRNA-1973 are the fruits of decades of investment into scientific research by the federal government, the private sector, and the hearts and minds of millions of scientists. While towering accomplishments, they represent a small sliver of the power of science. Only through science could we deconvolute the genetic sequence of a microscopic, unseeable particle in a matter of days. Only through science could we harness mRNA—the very nucleic acid that ferries our cellular genetic information—to create a vaccine candidate within weeks. Only through science could we have saved even the most ill on ventilators. Only through science could we run controlled, legitimate clinical trials across the globe to evaluate if these vaccines worked. As Darwin once said on biology, “There is a grandeur in this view of life.” I hope that in the wake of the coronavirus, all people will appreciate science.

In concluding his New York Times article on the discovery and development of these vaccines, Carl Zimmer captured the euphoria of Moderna’s positive data for Stephane Bancel. “He [Bancel],” he writes, “ducked out into the hallway to tell his wife. His 18-year old daughter raced down from the second floor. His 16-year old flew up the basement stairs. ‘The four of us were crying,’ he said.” In just a few weeks, when I will be one of the first worldwide to receive a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, I, too, might cry. We fought back a threat to our very existence. We made the world a better place. We did the impossible.

Rohan Shah is Chief of Staff to the Chief Operating Officer of Loxo Oncology at Lilly, a biotechnology company discovering and developing novel cancer medicines. He recently graduated from Princeton University with an A.B. in Molecular Biology and a Certificate in Entrepreneurship. He is based in New York City and can be reached at rshah@loxooncology.com. Special thanks to Tomi Lawal, Jordan Salama, Tiger Gao, and Policy Punchline for editing.